Rianat Ademola

While we insist that colonisation has transformed our lives, making us more liberal in the global space, we must not forget that it has stripped us of our dignity and our Africanness. Westerners are frequently charged with the responsibility of telling stories about Africa with a diminishing, negative image. As Chimamanda Adichie aptly put it, “stories of catastrophe”. It is only later that African writers take on the cloak of courage to change the narrative, using their artistic talents to restore our dignity.

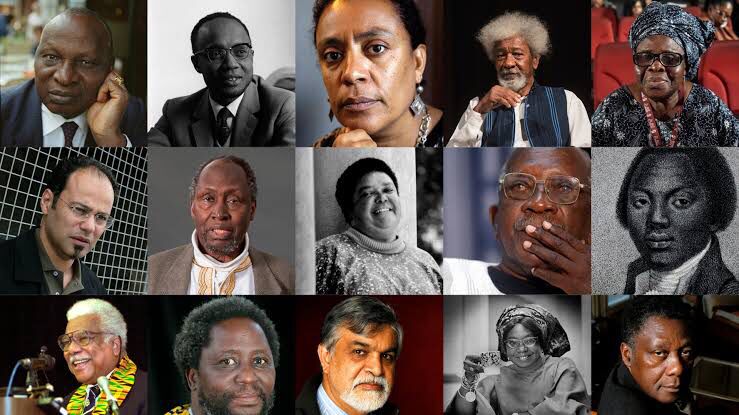

It is commendable that many authors have contributed to the corpus of African literature, but, ironically, even well-known names remain unfamiliar to many. While this may be understandable for students outside the Humanities, it is unacceptable for those within the field to lack awareness. Aside from the legendary Chinua Achebe and the sophisticated Nobel Laureate, Wole Soyinka, many students are oblivious to other African writers. In contrast, students are often well-versed in the lives and works of Western authors. Why is this the case? The answer lies in the fact that these African writers and their life stories are not prominently featured in our classrooms.

These writers are not fictional. Instead of being studied for their distinguished personalities, impact, or idiosyncrasies, African authors are often clumped together like sardines in a tin. They have stories to tell. We know from history how some of these writers were imprisoned, but we want to know more to satisfy our curiosity. Who exactly are these writers? What led to Soyinka’s imprisonment? Why was Ngugi wa Thiong’o arrested in Kenya? Who were the pioneering writers of African literature? It would be dishonest to claim that we have not encountered their names in class, but it would be equally untrue to say they are studied with the same depth and respect as Western writers.

Such stories about African writers’ struggles for independence need to be told distinctively. Most of us never had the luxury of meeting pioneering writers like Chinua Achebe, Kofi Awoonor, J.P. Clark, Gabriel Okpara, or Elechi Amadi, with the exception of Wole Soyinka. However, their works and lifetimes left indelible footprints in our history. The 1960s, for instance, was a remarkable literary era. It piqued our curiosity about what it cost these writers to tell their stories, truly and truthfully. Writers from the 1970s to the 1990s, such as Niyi Osundare, Sefi Attah, and Femi Osofisan, countered military discourse through their works. Yet, these writers often feel alien and distant to us, cramped into rigid African/African American literature curricula that fail to present them as individual entities.

The period from colonialism to the present should be a definitive course of study. We read and discuss papers on different regions of the world, analysing and comparing literary periods and authors. Yet, the archives of our beloved African writers are only read in passing. They are rarely given the attention they deserve.

African universities understandably keep students abreast of Western traditions due to colonial legacies, much like Ezeulu in Arrow of God, who sent his son to learn the ways of the whites, only for his son to become indifferent to his own culture. We left our cherished garment wrinkled for the sake of a new one. This approach narrows our view of the continent. We cannot afford such a narrow view because it makes our story incomplete. While the study of Western writers is not inherently problematic, it becomes an issue when it overshadows the exploration of African voices. This reinforces a colonial mindset, devaluing African traditions and knowledge. The solution is a balanced curriculum that equally emphasises both African and Western traditions.

The works of pioneer African poets and writers should not only be read but critically studied as a dedicated course. Who were these writers who learned how to say things unsaid and ask questions unasked? Their stories are not merely about writing books; behind them are great personal sacrifices and even the loss of life. Take, for instance, Christopher Okigbo, the vibrant and altruistic poet who died in the Biafran War, or Kofi Awoonor, who died during a war. These writers deserve to be studied in depth.

Literature is unique because it reflects us back to ourselves. Yet, in focusing too heavily on others, we risk casting away the essence of who we are. As Chinua Achebe wrote in his essay, African Literature as Restoration of Celebration, “African literature is a body of writing which in our lifetime has added an important dimension to world literature.” These are the people whose stories reflect who we are.

Retaining a colonial curriculum holds little interest for avid lovers of unexplored Africa. Despite geographical proximity, Africans often know little about one another, whether in literature or culture. This lack of awareness extends to geography, many are unsure where Namibia or Zimbabwe is located. To cap it all, we need to know more about ourselves. If we embrace our Africanness, if we study these writers, the beauty of our paradise will be regained.

Leave a comment