Ayobami Atanda

Some groups, organisations, as well as higher institutions of learning set up a lot of programmes and activities to celebrate Wole Soyinka as he clocks 90. Parts of the programmes and activities are the Yoruba adaptation of his play Death and King Horseman titled Iku Elesin Oba staged in Wole Soyinka Amphitheatre, University of Ibadan, the documentary of how he was taken to prison and brought back titled Ebrohimie Road organised by Institute and African Studies and the Department of English, University of Ibadan, and a movie show titled Eni Ogun translated to A Noble Warrior in Lagos. Wole Soyinka International Cultural Exchange, a socio-cultural international group established to globally erect Wole Soyinka’s cultural, social, and political dispositions organised some events in Nigeria and abroad in felicitation of his 90th birthday. The group organised an essay competition titled Wole Soyinka @ 90, The Many Lives Of An Irrepressible Patriot, Humanist, And Activist: it is translated as Eni Ogun in Yoruba.

The reverberating celebrations, accolades, applause, commendations, and recognitions that Wole Soyinka received stemmed from his being an irrepressible patriot, humanist, and activist. Since he graduated from college to this moment, he has shown to be a man for the people. He fought the whites during the colonial era in Africa and saw the end of colonialism. Shortly after Nigeria gained independence, he changed the subject matter of his works from writing against the whites’ exploitative, imperative attitude toward the Africans to writing against and confronting re-colonialisation and neo-colonisation of the blacks leaders on their fellow black people. In the same vein, he fought the civilian and military government. He fought every man who tried and wanted to oppress people. Soyinka stood against the annihilation of the Igbos during the Civil War from 1966 to 1970, which made him go to prison. Year in and year out, he spoke against any anti-freedom policy of the government. With his bravery by using his pen to pick a fight with ammunition, it cannot be overemphasised that Wole Soyinka is Eni Ogun, a noble warrior.

From Ibadan To United Kingdom

Much was not recorded about Wole Soyinka’s activism in his early days as a child of Mrs Aina and Mr Femi Soyinka in Abeokuta; he began his humanitarian struggles, not when he was admitted to University College, Ibadan, now the University of Ibadan nor when he was at Leeds University in the United Kingdom where he barged a degree in English, but when he graduated from college. However, when he was in Ibadan, in the Department of English, Wole Soyinka showed his unflinching love for dramas. He participated in a lot of theatrical acts and wrote some stage plays. His later development in the act is a buttress of all that he did while in Ibadan. His sojourn in University of Ibadan, as a student of English Literature, immersed him into the world of literature. Having studied the texts of prominent English and classical writers, he developed his profound love for literature. He chose drama as his favourite, though his artistic prowess in prose and poetry cannot be underestimated.

Wole Soyinka’s journey to the University of Leeds, United Kingdom, brought his knowledge increase and shaped his view about whites, which made him understand that no culture or race is superior to the other. His consciousness of intrinsic survival plunged him into his writing confrontation against colonialism and the elevation of his indigenous culture. He did not get lost in the labyrinth of the complexities of Western culture and imperialism, he stayed with Afrocentrism — making Africa the thematic centerpiece of his works of art. Furthermore, his journey to Leeds helped him secure employment at the Royal Court Theatre in London, where he worked as an editor.

The aggregation of his literary knowledge and experience garnered in Ibadan and Leeds birthed his appearance as a socio-political writer and critic. After graduating in 1958, he wrote The Lion and The Jewel (1959), A Dance In The Forest (1960), The Trial of Brother Jero (1960), The Strong Breeds (1963), The Road (1965), Konji Harvest (1966), Madmen and Specialists (1971), Death and the King’s Horseman (1975), just a mention a few.

To Gowon’s Prison

Wole Soyinka used his early literary works to fight against the inherent nature of the Western world to dominate others. He campaigned against colonialism. In his Death and The King’s Horseman, Wole Soyinka emphasised the need to allow each race to learn their survival method without any form of interference. His fierce opposition to colonialism and inclination towards Africanism made him write to sensitise his fellow blacks about the domineering attitudes of the Europeans, the need to embrace traditional culture and language, and the essentiality behind the independence of all African countries.

Immediately after Nigeria gained its independence in 1960, the nation began to pass through unprecedented agony caused by its leaders. There were cases of embezzlement of funds, rigging of elections, internal wars, states of emergency, coup d’etat, and assassinations, among others. Nigeria got freedom from the imperialist colonial master only to enter into aggravated woeful experiences, agony, and unbearable tragedies. Against the backdrop of the post-colonial events, Wole Soyinka delved into writing about socio-political issues, not only in Nigeria but all African nations, since the problems are Afro-demic. He once told the federal government to annul the Western region election as a result of irregularities in a radio broadcast of the Western Nigeria Broadcasting Service (WNBS).

In the wake of the Ojukwu-Gowon inimical tussle, which, like a wildfire, escalated into a civil war, Wole Soyinka, as a humanist and patriotic activist, berated the pogrom in Nigeria, which, in the end, took the lives of no fewer than 3 million people, according to Chinua Achebe’s There Was A Country. He criticized the then-military government, Yakubu Gowon, who was not ready to cease fire. Hence, Yakubu Gowon put him in solitary confinement for 28 months.

In 2024, Yakubu disclosed the reason he incarcerated Wole Soyinka, “When I was Head of State, he (Soyinka) did not want anything in uniform, and reports reaching me were that he was doing everything to effect a change of the system. I was told by some people that I should make sure that he (Soyinka) did not circulate much. At that time, he was very, very young; he had no grey hairs, perhaps what happened to him (his imprisonment) might have caused this his numerous grey hair. Both of us were very young and idealistic at that time and I happened to be the man in charge of Nigeria at that time. The tiny young man was trying everything he could to disrupt the normal process. We sat down and decided he must not circulate anymore because we thought he was then becoming very dangerous to the system, so we proffered what could be done to him. So he was my guest for two years and four months.”

Not only in Gowon’s era did Wole Soyinka take his stand with the people but since 1960 until this moment. He fought Major General Sanni Abacha for killing a democratic president-elect, M.K.O Abiola and other tyrannical acts. Years after the gruesome murder of Abiola, Soyinka refused to be honoured with Abacha. He rejected the Centenary Award in 2014 because Abacha’s name was on the list of awardees.

Soyinka said in a note of rejection headlined The Canonisation of Terror, “I can’t think of nothing more grotesque and derisive of the lifetime struggle of several of this (Honours) List and their selfless services to humanity”, Soyinka said in a statement entitled, `The Canonisation of Terror’. I reject my share of this national insult.”

“Such abandonment of moral rigour comes full circle sooner or later. The survivors of a plague known as Boko Haram, students in a place of enlightenment and moral instruction, are taken to a place of healing dedicated to an individual contagion – a murderer and thief of no redeeming quality known as Sani Abacha, one whose plunder is still being pursued all over the world and recovered piecemeal by international consortiums – at the behest of this same government which sees fit to place him on the nation’s Roll of Honour!”

To Stockholm

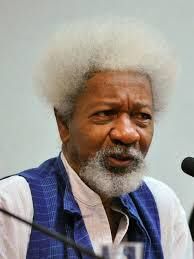

Soyinka in Stockholm, Sweden, 1986.

Wole Soyinka became the first African to scoop the Nobel Prize in Literature. In the press release of the Swedish Academy in 1986, it claims Wole Soyinka “He possesses a prolific store of words and expressions which he exploits to the full in witty dialogue, in satire and grotesquery, in quiet poetry and essays of sparkling vitality. Wole Soyinka’s writing is full of life and urgency. For all its complexity it is at the same time energetically coherent.”

His being awarded the most coveted award in literature was borne out of his vastness in literature by thearterising poetry, localising dramatic elements of Elizabethan drama in his works, rich display of African culture and Yoruba language, relentless confrontations against tyrants in his publications, wits, and conceits, amidst others. He flourishes in all genres of literature as he satires each of his immediate society in conformity with humanity.

The Eni Ogun — A Noble Warrior

Since the period of colonialism, Wole Soyinka has been at the forefront of the wars to liberate the citizens. He has been at the receiving end of his intellectual harangues concerning speaking for the people. He went on a voluntary exile in 1971 due to the cruelty of the leaders against the masses. He has been vilified, subjected to emotional torments, and confined for more than 2 years for a noble cause. He cried when people were oppressed and stood for them at the expense of his life. He could have been killed during the Civil War. The military government in 1996 could have killed him as well, but Wole Soyinka would not at any time give in to repression and oppression. He often comes out triumphantly against all the human oppressors. He is truly Eni Ogun.

Leave a comment