Adeniji John Taiwo

Observably, the human society has been engineered to differentiate between groups: male and female, old and young, rich and poor, black and white, the learned and unlearned, among others. These alternatives makeup indices against which language variation can be measured. While these indices lay bare the boundaries for individual in terms of what they can and cannot say, breaking the gulf by any of the groups on either side of the divide leaves one with much water (consequences) on their heel than the other: in some cultures, supra societal means sanction females’ express discussion of genitals-related topics, but there are no sanctions for men —for the men, it is just something to revel in; what passes as the immaturity of a lad may “land” an adult in serious trouble. A rule of thumb in this regard is to mind one’s language; thankfully, social variables serve as soldiers that uphold this mantra. These social factors include:

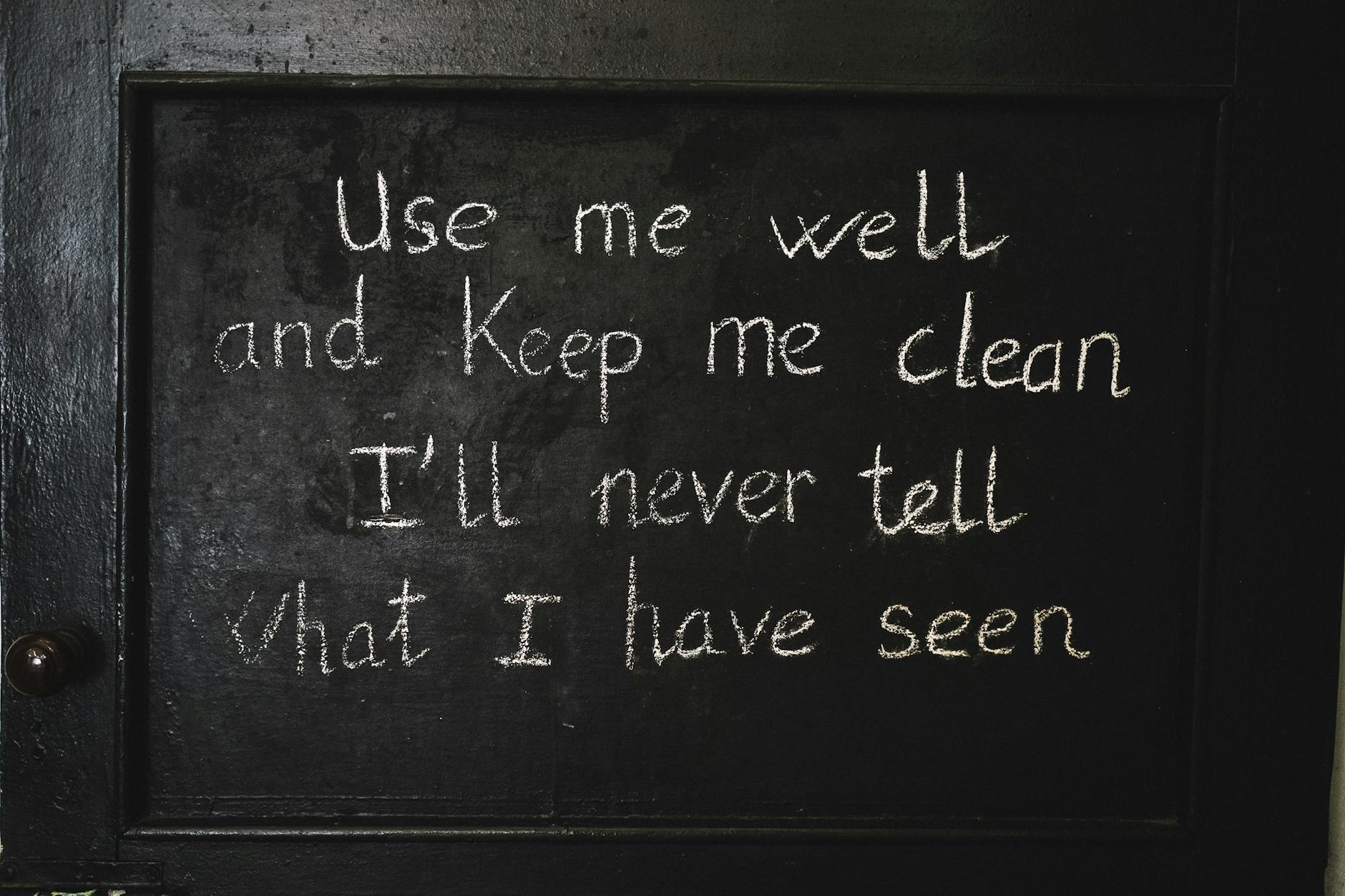

Age: In terms of age, language use varies between the young (children and adolescents) and adults. Clear distinction can be made in terms of the preponderance of slangy expression amongst adolescents. Frequently used slang by Nigerian youth include “aza” (bank account detail), “chop” (to eat), “palava” (problem), “kuku” (simply), “bad belle” (a jealous person), etc. It gets more interesting when youth communicate using slang to avoid divulging their secret to the adults. Since it appears everyone is busy hiding something from the other, the adults are masters of their game when it comes to the use of proverbs and euphemistic expressions in concealing details. A typical yoruba person who has been sent on a fool’s errand of getting “àródan” can better relate. It appears then that the wise accounts for lost words with proverbs which in turn confers an outsider status on another, obscuring not-to-be-shared details.

Sex: considered in terms of the biological distinction made between male and female, constitutes a set of features that foregrounds language variation amongst individuals of different classes in terms of sex. The distinction between male and female and what group a person belongs is a key determiner of what can or cannot be said. In most cultures, the repertoire of women’s vocabulary is expected to be made up of terms indicative of their submissiveness. Otherwise, a woman, in the said culture, may appear disrespectful. On the part of the male, societal expectations impose patterned modes of language use such as the use of more assertives; a man does not solicit for respect neither does he lobby for it, he commands it. This is only one out of numerous belief systems instituted by society that influences the way different sex use language differently in different situations.

Education is a legacy indeed: it leaves many with such air of superiority as to confound the already confounded. For example, “High-soundedness”, as I would love to call it, is an aspect of educated English that can not be underestimated. Educated people use language in a more formal way than uneducated people. In fact, among the educated, language use varies depending on the level of education an individual has acquired.

Ethnicity: the Oxford Advanced Learners’ Dictionary defines ethnicity as “the fact of belonging to a particular ethnic group —a group of people that share a cultural tradition.” As ethnicity captures culture which in turn entails human beliefs, the difference in individual belief systems across different cultures and ethnicity influence language variation. In the English language, the color green may, in its own right, serve as a hypernym with subordinates as “teal green”, “neon green”, “light green”, “army green”, etc. For a speaker of Yoruba, a Nigerian language of the Niger-Congo language family, these subordinates are termed “àwọ̀ ewé” meaning “the “colour of a leave”. As such, a second language user of English who is of Yoruba background is likely to, on the basis of the foregoing, refer to the different shades highlighted in a single term, “green.” It is safe to argue that ethnicity shapes perception and perception shapes language use.When next you ponder on why an individual spoke the way they did, except on the basis of other grounds not discussed here, you may want to consider the variable highlighted and pinpoint which is responsible for such individual’s choice. The watchword remains, “mind your language.” You might want to consider speaking your age, sex, ethnicity, education among others. It will save you some stress. This however is not a call to bow to societal biases. The ball is in your court.

Leave a comment